This is, hands down, the best hand-sanding block I have used. What I like best is that the substantial weight, the thoughtfully designed contours, and the 7 3/4″ x 2 3/4″ dimensions combine to give it a purchase in my hands that resembles a small wooden smoothing plane. This feel, plus the outright effectiveness of the tool, actually raise the dignity of sanding.

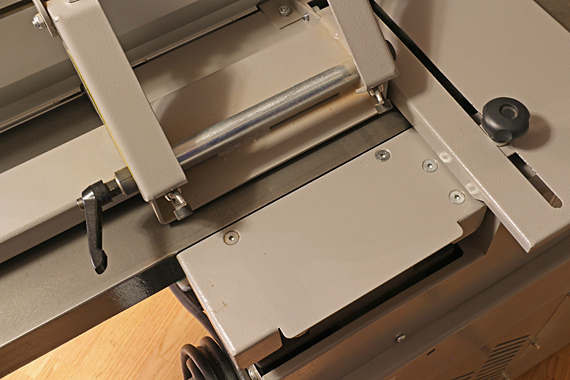

It is also very practical. It is fast and easy to clamp strips of 2 3/4″-wide paper, which are produced by three tears across the width of standard 9″ x 11″ sheets. (Here’s how to make that easy.) The clamps grab a strip near its ends so there is minimal waste. You can install multiple sheets and tear them away in succession but I prefer the feel with a single layer of paper. Now is a good time to restate my opinion that 3M is the clear winner in sheets for hand sanding.

Long accustomed to my cork blocks, I bought the Preppin’ Weapons on a whim, but for all but small-scale work, I now favor them over the corks. I suggest buy different color Preppin’ Weapons to code the installed sandpaper and make jobs move along faster.

Now for an idea or perhaps a bit of insight into some of what happens at the sandpaper-wood interface. We know that a smoothing plane blade with a straight edge and square corners will promptly produce “gutter” marks on the wood surface, which are slight steps across the width of the board. To eliminate this problem, we sharpen the blade with a very slight curve (camber). This actually makes imperceptible waves that pretty much cancel each other with successive passes of the plane as the peaks of the waves are shaved away. Note that the depth of the blade camber is coordinated with the anticipated shaving thickness. The result is a surface that is, for all practical purposes, nice and flat.

Similarly, imagine a hard block of steel used as a sanding block, especially with substantial pressure. Of course, no one would use that. It would create tiny gutters or steps, and the process of erasing them would just produce new ones.

The cushion, or resilience, of the bottom surface of a sanding block – cork, rubber, or foam – solves this. With variable hand pressure, we must be producing miniscule waves (probably variably oriented) that get evened out with successive strokes, leaving an essentially flat surface. We never see steps. We intuitively use a little more pressure with coarser paper, inducing more flex in the sanding pad, analogous to coarser plane shavings. Finer sandpaper and less pressure give more shallow waves and ultimately we end up with a nice flat surface.

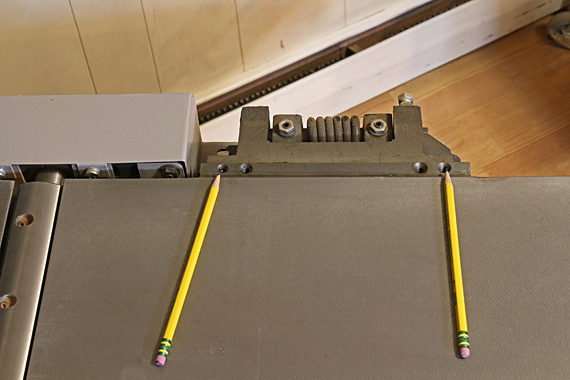

Coordinated with the area of the contact surface, the flex of the 5/32″ foam pad on the base of the Preppin’ Weapon is just right for producing a smooth and true surface.

This tool gets everything right.