Kinex squares are a fantastic value. Not well known to U.S. woodworkers, Kinex’s website states, “Swiss quality made in the Czech Republic.” Their tools are made to German DIN standards for accuracy. That’s the Deutsches Institut für Normung, which just sounds accurate to my ears.

Their all-steel “Precision Universal Squares,” which are designed much like a regular try square, are available in DIN 875/1 or the even stricter DIN 875/0. Each square comes with its own signed inspection certificate.

As examples, a 150mm (6″ blade) square in the DIN 875/1 standard has a deviation-from-right-angle tolerance of .018mm (.0007″) and costs $15.99 on Amazon, sold by Taylor Toolworks. The 150mm DIN 875/0 has a tolerance of .008mm (.0003″ – about a quarter thou!) and costs only $19.99. You can also order Kinex tools directly from Taylor Toolworks.

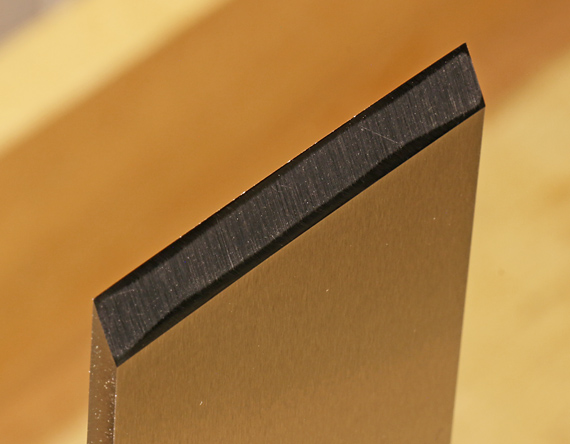

The handy 100mm x 70mm square (model #4026-02-010, DIN 875/0) that I bought is nicely balanced, and well finished with all edges relieved. There was a tiny nick on the blade and a tiny burr at the end of the blade, both of which I easily removed with a fine diamond touch-up hone. There were also a few insignificant surface scratches.

I cannot truly assess this level of accuracy in my shop but testing against my Starrett showed virtually light-blocking consistency in all parameters. I’m happy because, as someone quipped in an article that I read somewhere, long ago, “I like to be the only one adding inaccuracy to my work.”

Kinex makes other models of squares – flat, stand up, knife-edge, large, and lightweight – and an extensive line of other precision tools. As far as I know, Kinex squares are not sold by any traditional or online woodworking stores in the U.S. except Taylor Toolworks. Kinex has an online store but shipping is from Europe.

As usual, this review is unsolicited and uncompensated. I have no relationship with Kinex or its distributors.

Update 12/19/20: I came to dislike and ultimately reject the 100mm Kinex square that I was using because of the relieved edges, especially on the blade. I found that these minute chamfers make it more difficult to see tiny deviations from square when placed against the work. By contrast, Starrett squares have crisp unrelieved edges that allow more sensitive assessment of the work. The Kinex are still very good squares at an incredible price, and the slightly relieved edges may not bother you at all. However, based on the edge treatment, I no longer can recommend them despite their several other merits including extreme accuracy.