Oops, I had a SawStop “event.” But it was not my flesh that met the blade. Rather, I foolishly forgot to reset the miter gauge fence when setting up an angled crosscut, and ran the aluminum fence into the blade, and . . . boomp! So, I had to send out the damaged blade for repair along with my spare blade that was damaged 14 years ago when I was setting up the new saw. This, plus buying a new SawStop brake, made for an expensive goof up. All told I’ve lost use of the tablesaw for four weeks.

But, I’m doing just fine, thank you. In fact, the episode has reinforced my longstanding conviction and advice that the tablesaw is not the key machine in the furniture maker’s shop. In my view, that distinction belongs to the bandsaw, especially when it teams up with a good thickness planer, or better yet, a wide jointer-planer combination machine.

Far from being a hand tool purist, I was happy ripping on the bandsaw with surprisingly little clean up required with a handplane. I also cleaned up lots of 15/16″-thick, 3″/3 1/2″-wide pieces by standing them on edge going through the DW735 planer with the Shelix cutterhead. I made sure the rollers and bed stayed clean, and it went well.

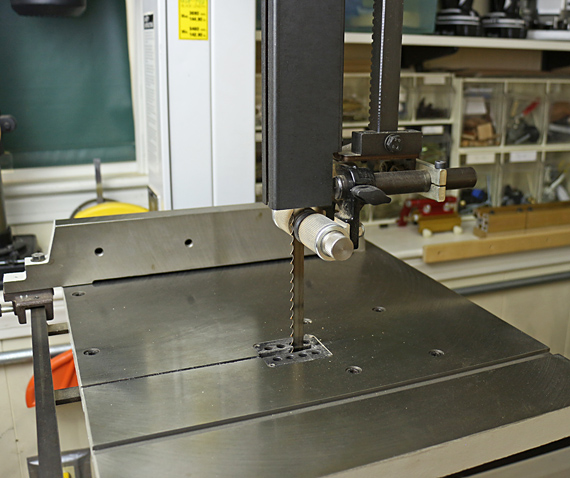

“What about crosscutting,” you say, “that’s not likely to go well on the bandsaw.” Well, using the little miter gauge that came with my bandsaw, the crosscuts are pretty accurate and not too rough even with my all-purpose 3-tpi blade.

Which brings me to another longstanding conviction and advice. And that is the importance of shooting. It was a pleasure to clean up the bandsawn crosscuts cleaner and more accurately than even the tablesaw could do. Shooting is so critical to accurate furniture making that I suggest sparing no effort and tools to set up good systems for end grain and long grain shooting. (I’ll describe my current long grain setup and have some tips in an upcoming post.)

I won’t be selling my tablesaw – it does a lot of tasks efficiently and well. However, I do want to reinforce this advice regarding machines, especially for woodworkers setting up or upgrading their shops:

- The first machine to buy is a good portable thickness planer. The DW735 has no peer.

- As soon as you can, buy the best bandsaw you can. Steel frame style, at least 12″ resaw height, preferably something close to 2.5 HP or more.

- Get a 12″ jointer if you can.

- And sometime, yes, you’ll probably want a tablesaw.

Most important, no matter what tools you have, build things.