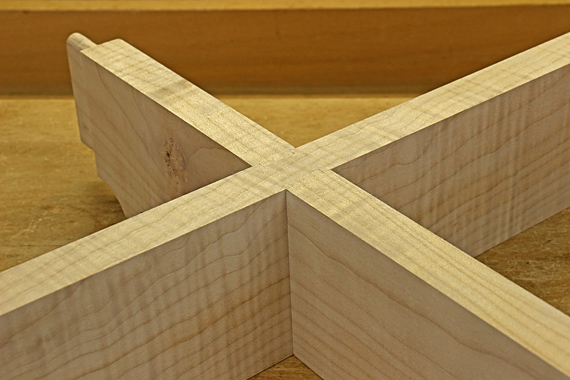

For rails that cross over their widths, this joint is very doable, strong, and neat. It has several advantages over other options for this situation. (Note this is distinct from rails crossing over their thicknesses, face to face, where the familiar half-lap is a good choice.)

Let’s take a look.

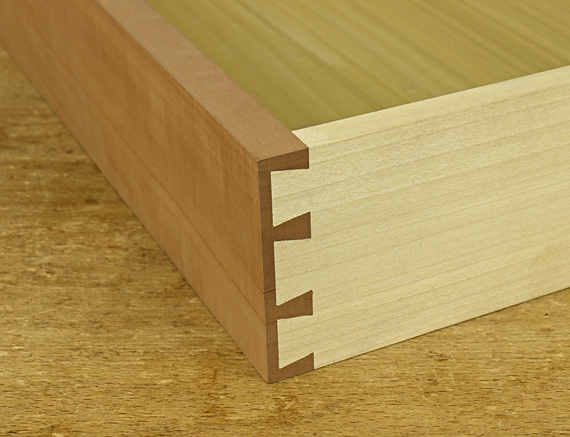

Each crossing member has strength distributed over nearly its full width, and there is no unsupported portion of the width. Furthermore, there is mechanical resistance to twisting in all directions. This is superior to a cross-halving (or “cross-lap”) joint, which is just a vertically oriented half-lap.

This is a strong joint with substantial long grain-to-long grain glue surface – more than 8 square inches. Note that the five dowels are long and continuous from one side to the other side of the joint. Cross-halving joints yield minimal long grain apposition.

It is much easier to conceptualize and execute this joint the than refined but elaborate cross-halving designs that involve stepped notches, sliding double-dovetails, or tapered notches. They make my head hurt.

For an enduring neat appearance as well as strength, the pieces entering the dado have outside shoulders. This differs from some versions of the cross-halving joint that are designed to correct the problem of unsupported width, and involve a dado that houses the full width of the entering piece, which can leave gaps when the housed member shrinks in thickness.

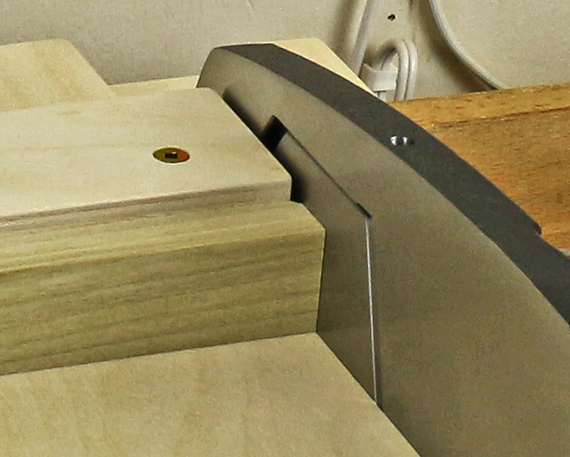

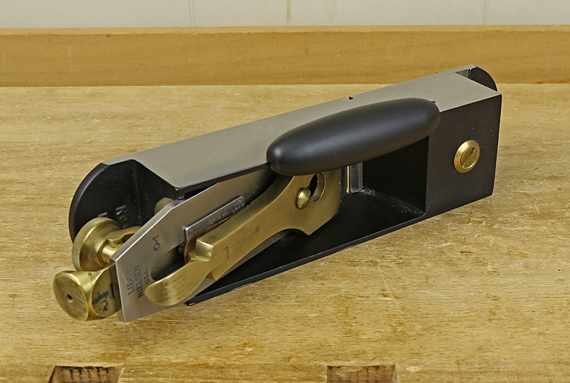

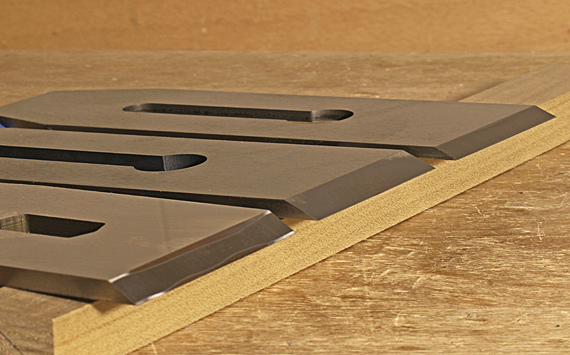

Woodworkers of all stripes will be pleased to know that this joint can be executed by hand, by machine, or a combination of both. In fact, you will see that a single shop-made jig can be easily adapted for use with various workpiece thicknesses and even various widths.

Full disclosure: a disadvantage is that it must be clamped from the ends. This could be awkward for very long pieces, though that is not a likely application.

Next: How to make it. As with all woodworking, it’s a matter of being accurate when it counts.