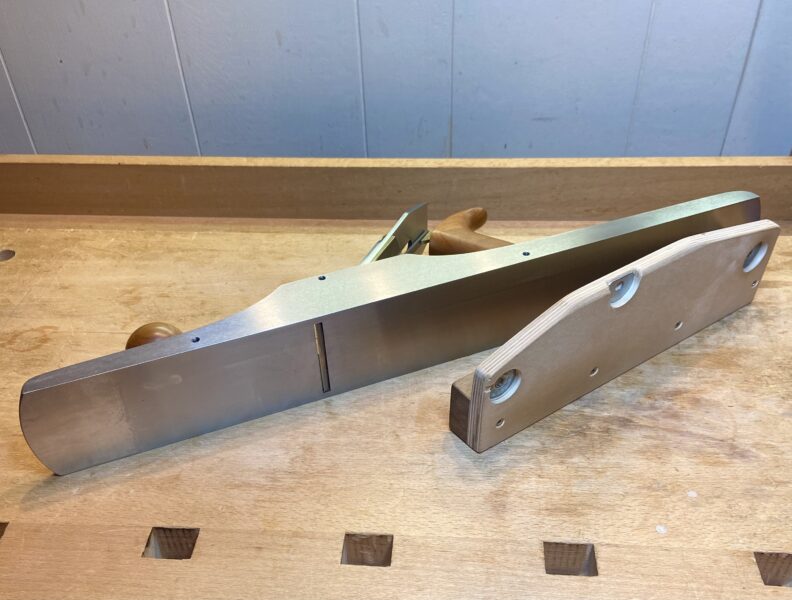

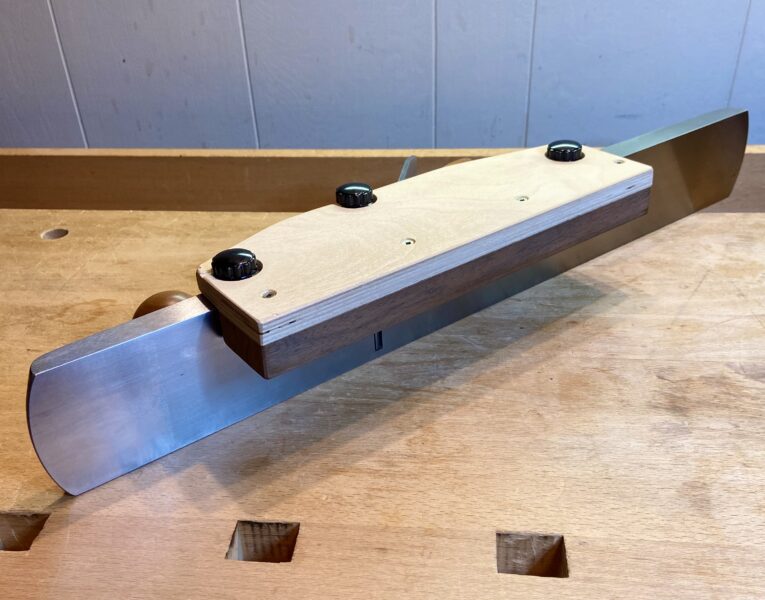

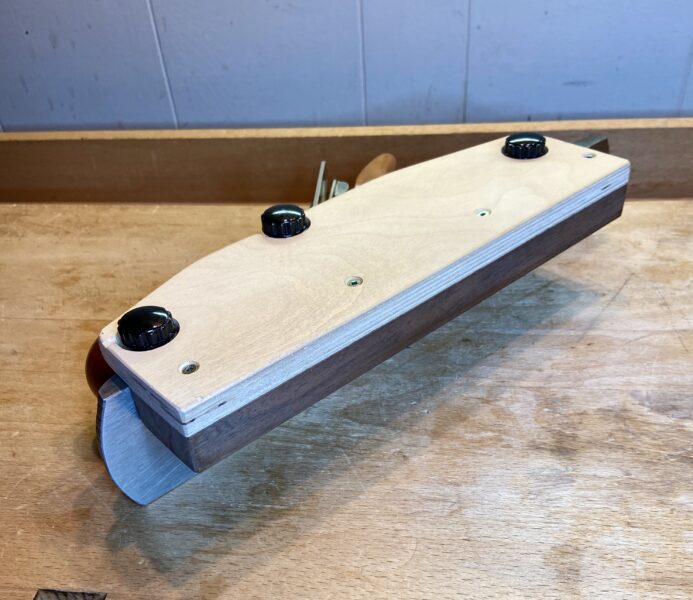

Here is the shop-made fence that I have been using since well before the current manufactured versions became available. It works very well for planing a board to a straight, 90° edge. Here is how to make it.

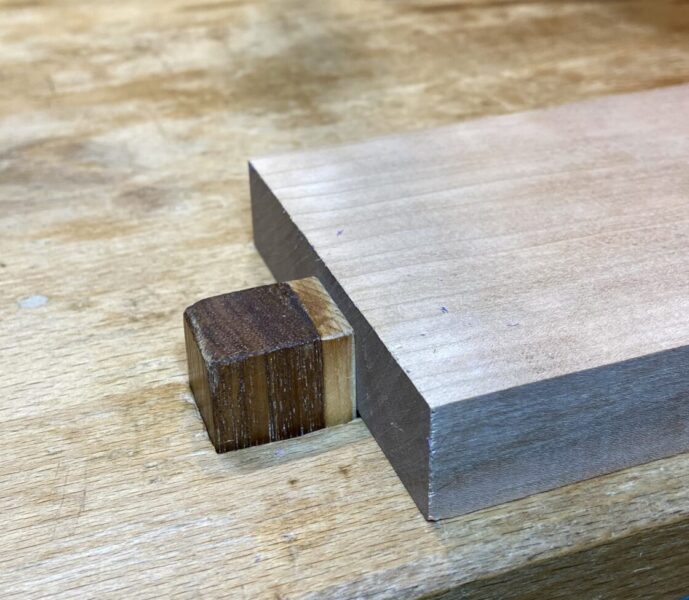

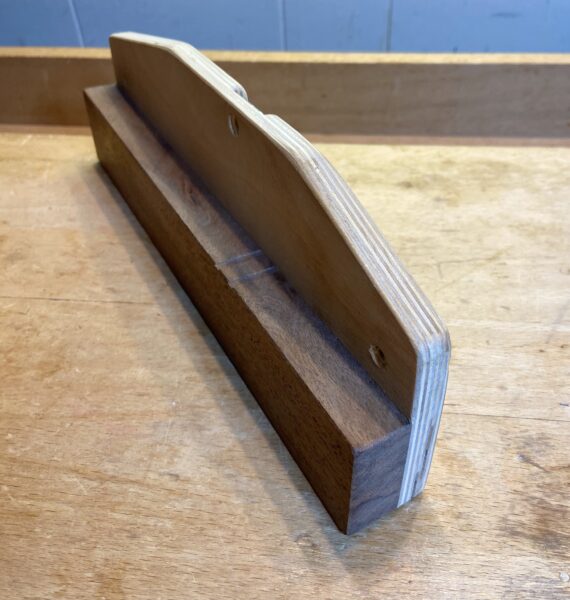

Start with settled dry wood. I used quarter-sawn walnut with a straight, even grain. It is 11” long, 1 3/4” wide, and 3/4” thick.

This 3/4” thickness of the guide will center the plane blade of a 2 3/8” wide (14” long) jack plane on a workpiece 7/8” thick. For a 2 3/4” wide (22” long) jointer, the blade is centered on a 1 1/4” workpiece. A better compromised wood thickness for the guide would be about 7/8”. That would center the blade on 5/8” work with the jack, and 1” work with the jointer.

However, the guide wood thickness does not need to be precise. Here is what is important: The jack or jointer blade edge should be correctly exposed in its width. The edge of these blades should be sharpened to extend very slightly more in the center than at the sides. Thus, set up the blade exposure so the cutting edge is very slightly more at the center of the workpiece width, and less at the sides of the workpiece width.

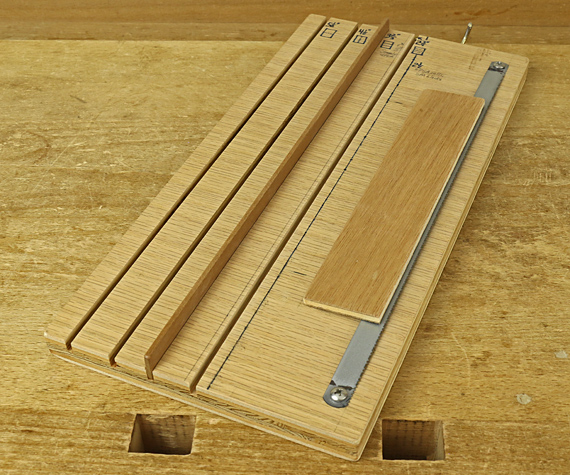

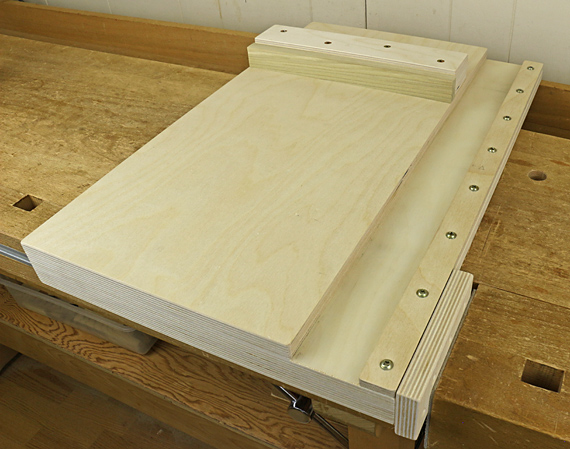

Ok, back to making the guide. See the photos. I used a piece of flat, high-quality, 11-layer, 1/2” thick plywood to attach to the guide wood with four screws. It is 3 3/4” wide, angled at the top edge. There are three 1” wide, 3/16” deep holes at the top to accommodate steel washers, glued in. Corresponding #10-24 1/2” thumb screws pass through the holes and screw into 10-24 drilled and taped holes in the plane wall.

It takes careful but not difficult work to set up this attachment system. It does no damage to the plane wall if set up properly.

There are a couple of very shallow, 1/8” wide slots in the top of the guide wood to accommodate the exposed cutting edge in the jack and jointer.

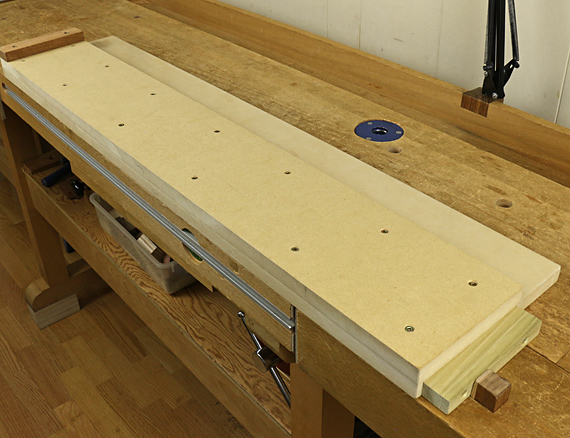

Additional note: With the new fence screwed onto the plane, check for square between the fence and the bottom of the plane. Carefully plane/scrape the outer face of the guide wood to get it perfectly square to the plane bottom.

To make accurate plane cuts with the guide, it is all about using your hands, shoulders, and body weight. (Assuming you sharpened the blade nicely!) The right hand pushes the plane with the index finger usually extended. The left hand lays over the side of the guide with the thumb at the top and the four other fingers and palm heel keeping it snug against the wood work.

At the start of the cut, the left hand thumb and palm heel can apply some pressure to the front of the plane. Then, in the long middle range of the cut, both hands keep light pressure over the whole plane. Finally, the heal of the right hand presses down at the curved lower part of the plane handle at the last part of the cut.

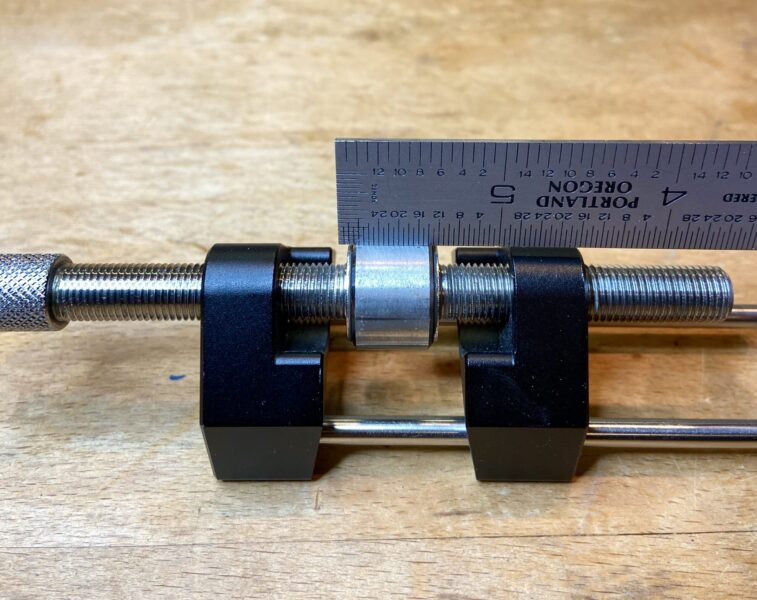

Well, I made this guide tool years before there were factory-made metal guide fences available. If you prefer, check out the several different plane fences made by Veritas: Jointer Fence, Bevel-up Jointer Fence, Technical Fence, Universal Variable Angle Plane Fence, Variable Angle Fence for Veritas Bench Planes, and Variable Angle Fence for Veritas Rabbit Planes. That is certainly more versatility than the basic guide that I show you here, but I still use mine after 40 years for 95% of my edge planing.

Now you have options. I do suggest to avoid doing the precise planing task without a guide.

Enjoy the work!