Hopefully, the drawer will close with the front even all around with the edge of the opening. If not, now is the time to correct this by planing. Soften corners to your preference. Cut a substantial chamfer on the top of the entering edges of the sides.

Closing stops can be installed at the front of the frame to contact the back surface of the drawer front below the drawer bottom. The strongest designs are those mortised into the frame. This generally requires the foresight to make the mortises before assembling the frame. (No comment.) They can also be glued, screwed, or even mortised to the frame near the end of construction, though less conveniently. To ease installation, it is helpful to design the stop with an abutting placement, such as against the back edge of the divider. The photo above shows a simple drawer stop design that hooks over the divider and is screwed to the back of it. The small undercut chamfer, visible at the front of the stop, facilitates fine trimming with a shoulder plane after assembly.

For all but the smallest drawers, two stops are best to create an unambiguous closure across the full width of the drawer. Since the drawer is then in a good, neutral position, it will be easy to open without jamming. I prefer the front face to be a hair inside the edge of the housing.

Alternatively, closing stops can be placed at the back of the case on the runners.

Outgoing stops are optional. A simple, effective design is a small piece of wood, screwed to the back of the drawer divider, which contacts the back of the drawer on its way out, yet can be rotated 90 degrees to let the back pass by to remove the drawer. (You know, to show your woodworking friends.)

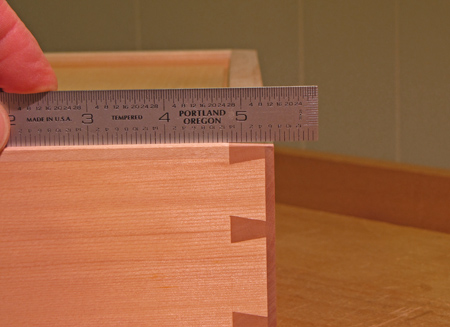

I like to bevel the bottom edge of the front of a flush fit drawer to prevent it from rubbing the bottom of the drawer frame. (The drawer is upside down in the photo below.) This way the drawer will run only on its sides. On very small drawers, it may look good to match this gap to the one at the top of the front.

The front is finished to match the outside of the piece. For the sides and back and bottom, think “less is more.” Personal preferences aside, there are a few points to keep in mind: avoid perpetually smelly oil finishes on the inside of the drawers or case, finish the bottoms before assembly, and avoid any film finish on the outside of the side pieces. A light coat of wax on the sides’ outer surfaces and bottom edges will help produce pleasant drawer action.

Next: getting a handle on it and closing thoughts for the series