Myth: a well-tuned handplane is the best choice for final wood surfacing prior to applying the finish

Reality: Sometimes yes, but it depends.

Disclaimer: Because I am the writer, “reality” is through my eyes. Yours may differ. I recognize an element of subjectivity in issues such as this. Nonetheless, the “myth – reality” approach has a nice jolt to it, and this blog is about woodworking, not metaphysics. (I work wood. Therefore, I am?)

The method to produce the most desirable surface on the wood prior to finishing depends on the wood, the finish that will be applied, and the physical circumstances of the piece.

This is best demonstrated by a set of examples.

A dense, hard, small-pore wood such as bubinga, with either an oil or a film finish such as varnish, will look every bit as good with fine hand sanding as with the most careful planing. A flat surface could be completed with planing or finished off with sanding, while rasps, scrapers and sandpaper could be used for a curvy leg. All will look equally good when finished.

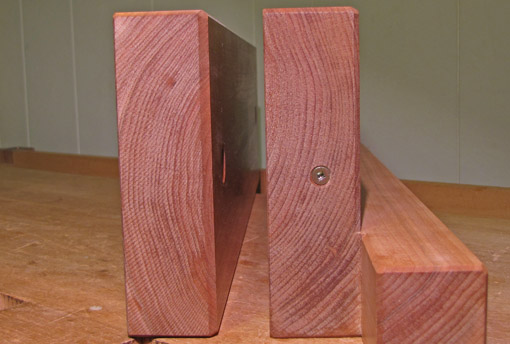

On the other hand, Port Orford cedar looks resplendent directly from a sharp smoothing plane, with a clarity that sanding cannot match. I like this beautifully fragrant wood without any finish.

What about curly big-leaf maple, one of my favorites? A well-tuned smoothing plane with a high cutting angle can handle it but I feel that sanding, finishing by hand with 320 or 400 grit, produces an equally beautiful appearance when the piece is finished with gel varnish, my preference for big-leaf. I use whichever method is easier for the circumstances.

Curly cherry is a difficult one. After experimenting with various samples, I am convinced that sanding muddies the figure, which looks inferior to the clarity produced by planing, and this effect persists even with a thin film finish such as padded shellac or wipe-on varnish. The same is generally true, though less so, for curly pearwood with a thin water-base acrylic finish.

Mahogany? I find that hand sanding and planing yield surfaces that look the same under shellac or varnish. This wood is so often rowey that I usually find it easier to complete the surface preparation with sandpaper. Oaks? Both methods seem to work equally well in most cases. Claro walnut? It depends on the figure and the choice of finish but I plane when I can since it does seem to preserve clarity when an oil finish is used.

There are other considerations, such as the peaceful, dust-free experience of planing. Planing is usually faster than sanding, maintains the trueness of a surface more reliably, and usually produces crisper edges. On the other hand, edge tools are often impractical for contoured work, yet we can use rasps, scrapers, and sandpaper to sensitively produce the desired shapes.

The point is that it depends! In making choices for surfacing, the woodworker has to consider the wood, the intended finish, and the circumstances of the piece, and may need to do some experimenting. You must be observant and make choices based on your concept of the piece, not on purist generalizations. Trust your perceptiveness and judgement, more than what anyone, including me, tells you.