It’s really not fair that I say that about wood. After all, I am forever cognizant of one of the first few sentences of Bruce Hoadley’s Understanding Wood : “Wood evolved as a functional tissue of plants and not as a material designed to satisfy the needs of woodworkers.” We cannot cut down the tree, cook the wood, and expect it to do just what we want.

Understanding is indeed the key to a successful relationship with wood as we work with what it is, rather than what we might wish it to be. One of the prime reasons a project can fall short of expectations is the failure to anticipate insidious changes in the wood.

For the top board of a cherry wall cabinet, I wanted a lengthwise curve in its thickness to produce an appealing motif borrowed from the Japanese torii gate. Starting with rough stock nearly 1 ½” thick and about 9″ wide, the final thickness at the center of the 25″ length will be just under 11/16″ and, at the outer ends, just under 1 3/16″, for a curve depth of ½”.

A simple approach would be to joint and thickness the rough board to a bit more than 1 3/16″, then cut and smooth the curve on one face. Done, right? Wrong. Removing a substantial thickness from one side of a kiln-dried board is almost sure to distort it, transforming the opposite flat face that was previously true into a potato chip that will wreak havoc with subsequent attempts at joinery.

We know from resawing wood that most boards retain some internal stress from casehardening. This usually causes the halves of a resawn board to cup toward the inner face. This is not always the case but there is a test for it. This is not a problem of moisture exchange. (Though that could also be present as another issue.) The stresses present in the dried wood cause it to occur even in a board with uniform moisture content through its full thickness. The distortion happens immediately after the board is resawn.

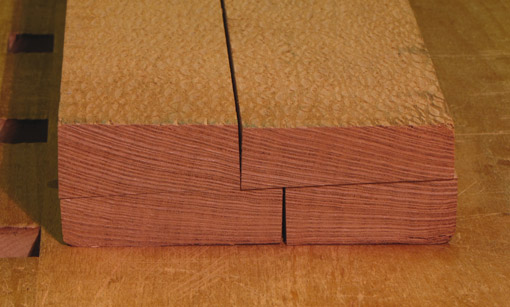

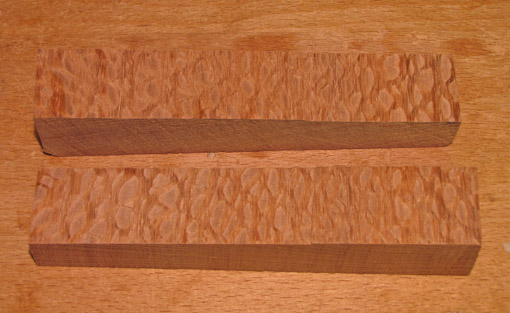

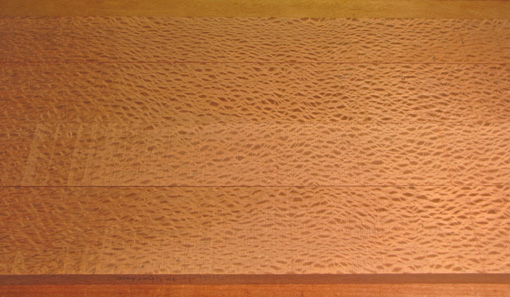

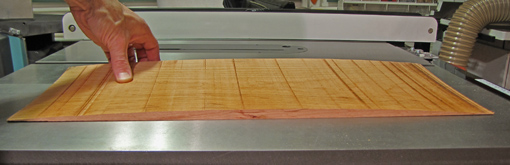

The photos below show the offcut within minutes after sawing. The outside face was flat before sawing. With that face placed on the table saw top, it can be seen that the piece has curved toward the inner (sawn) face in both along its length and across its width.

I’ve left out some steps which I will show in the next post. With this board, I did not have much extra thickness to work with after getting past the rough sawn surfaces, so I needed to anticipate what the wood had in store and have a good plan going in. I will detail the solution in the next post, though I think most readers will be one step ahead of it.