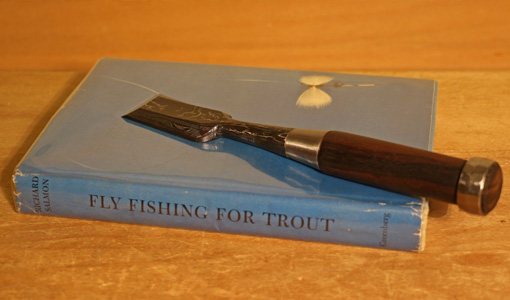

Early on the long road to proficiency in a craft or any serious skill, there are many mysteries to solve. In this first stage, there are countless individual elements that are difficult to master and all together they can seem overwhelming. For example, the vast range of tools can be paralyzing for a novice woodworker, and to make matters worse, most new tools must be tuned or sharpened before they can even work properly.

Gradually, each element is conquered and these early mysteries dissolve. Despite this progress, there is a growing feeling that, “I know what all the buttons do but I can’t get the thing to work.” In other words, the elements still must be synthesized – another set of mysteries to solve. In this second stage, the developing woodworker who has learned to use all of the tools and make joints must still learn how to integrate many skills to actually make a piece of furniture.

This is the big picture and it is becoming clear. Now you know what you are doing and you know it. You can really make stuff. With continued ambition, more practice, and, of course, a fair share of missteps and even disasters, you can make better stuff. There will always be lots more to learn but the big picture is no longer a mystery.

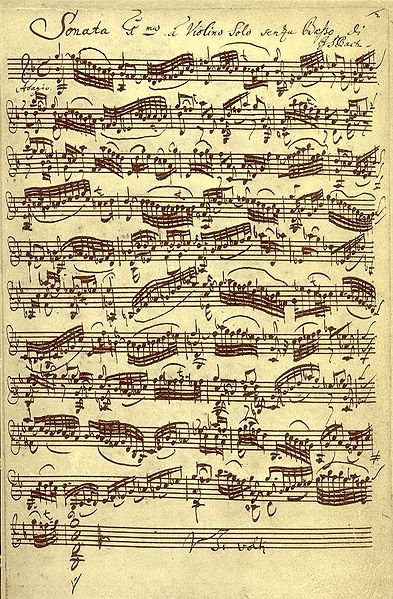

After all of this comes a mystery of a different sort, an important one that is actually welcome and is meant to persist. The skillful person is now doing some things without being cognizant of why, at least at the moment, yet the moves are very right.

It is as if the program, so to speak, runs on its own – not always, but at least during some of the most productive times. Call it instinct, flow, intuition, grooved neural pathways, or just a lot of plain old practice, but there is indeed a wonderful mystery to it.

Sure, this happens during some days or hours and quite disappointingly not during others. Moreover, some flights of supposed brilliance could be very wrong, though that is a risk hopefully worth taking.

Here are some examples.

- Watch the great soccer player Neymar. He is surely not aware at the time of exactly how he makes split-second moves on the field, and even afterwards probably cannot fully explain his mental processes.

- All the studies and data in the world will never fully supplant the instincts of an experienced medical clinician or a financier, each faced with the unique specifics of a case at hand.

- A craftsperson’s hands seem to have mind of their own.

- A very good every day driver may save his life with a moment of prescience, and NASCAR drivers probably do this all the time.

- A good teacher knows with a sixth sense how to reach each student as an individual.

- Most wonderfully, a refined creative sense tells us that when it feels right, it is right.

So OK, this is a very good place to be but what of use can be said about it? After all, it is a difficult matter to deconstruct. Certainly, reaching this level is not easy and requires time, practice, and talent.

I think most important is the realization that this level of functioning cannot be borrowed or directly taught. This form of doing something truly well must arise uniquely within each person after the first two stages have been taught and learned.

This happens as you train, practice, and confront the expanse of your freedom with courage. This learning grows in the quiet moments of concentration when persistence seems inevitable and you trust yourself even if the effort is uncomfortable. With humility and some luck, mastery may be ahead.

The late, great basketball coach John Wooden said, “It is what you learn after you know it all that counts.”

Readers of this blog may have noticed that the author has a few pet peeves. Among them are

Readers of this blog may have noticed that the author has a few pet peeves. Among them are