This is the best shooting board I have ever used. I believe it is probably the best available anywhere. Tico Vogt made it and he can make one for you – the Super Chute 2.0. A shooting board is an extremely useful, almost magical, tool that can greatly elevate your control of woodworking processes. After watching Tico develop and improve his version of this tool, I finally had a chance to use it last week at a Lie-Nielsen Hand Tool Event at the Connecticut Valley School of Woodworking.

That’s Tico in the photos using his Super Chute 2.0.

It was like slicing baloney with a sled on an ice track. Tico showed me the tool’s incredible quality details and nuances that only could come from a seasoned woodworker who knows from experience what really works in the shop. To elaborate on all of them here would make this post too long, but I will point out a few highlights.

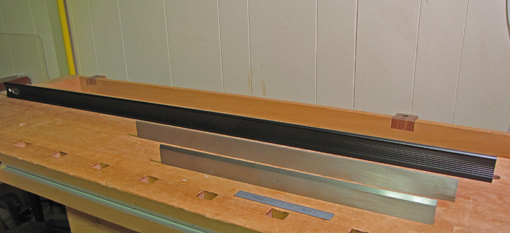

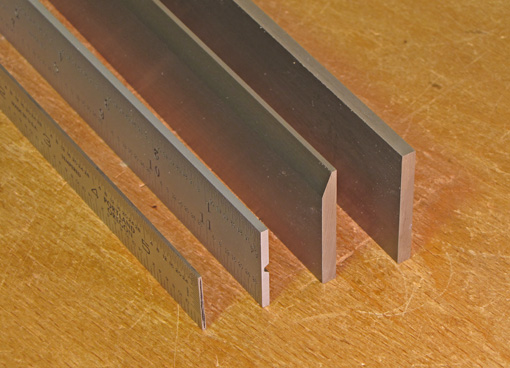

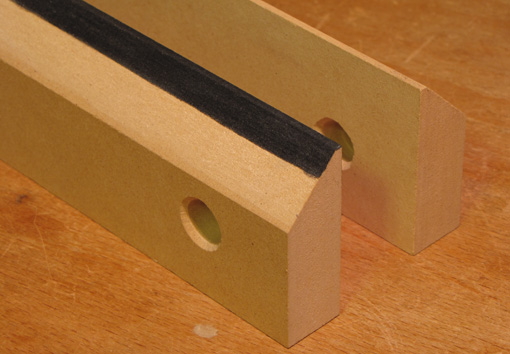

The plane rides on a track of super-slick UHMW plastic. Importantly, the work piece sits on an angled bed which facilitates a strong stroke with the plane and distributes wear and cutting resistance over a greater width of the blade than a flat bed would. The 90̊ and instantly-installed 45̊ fences register in eccentric bushings which make their angles micro adjustable. The fences are also laterally adjustable to completely eliminate end grain spelching. To my mind, these user-controlled features respect the skill and intelligence of the craftsman using the tool. A donkey ear miter attachment that installs easily is also available.

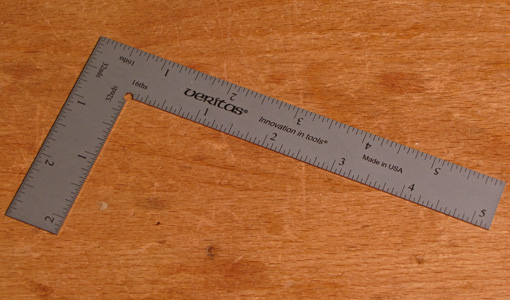

Tico uses CNC technology and sources components manufactured with a high degree of sophistication to a produce a product with quality evident throughout. No, it’s not cheap; excellence never is. This is Lie-Nielsen-type quality in a shooting board.

A plane such as L-N’s sweet #9 makes shooting all the more of a pleasure but don’t feel you must have a dedicated miter plane to start shooting. A well-tuned and well-sharpened jack plane, bevel-up or bevel-down, can shoot very effectively. Shooting is a gateway technique, easily learned, that will allow you to produce precise ends on components of casework. It is a must for making precision high-end drawers with hand tools.

This review is unsolicited and uncompensated. I just think the Super Chute 2.0 is a heckuva tool.