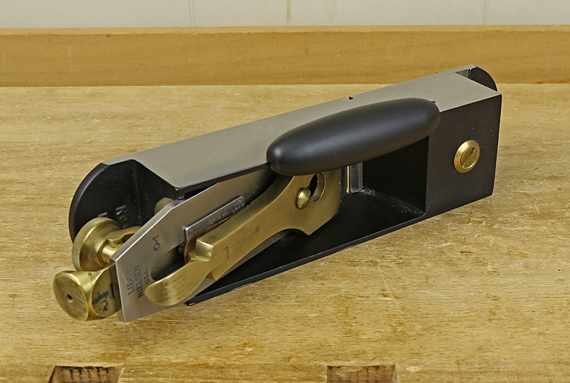

Another question from a reader: “My trouble in shooting is (I guess) in advancing the wood. I often find myself in a situation where I’m feel like I’m pushing the wood very firmly against the toe of the plane and still not getting any bite from the blade. This problem seems to come and go and I have yet to diagnose what I’m doing wrong.”

There are at least two possible reasons for this.

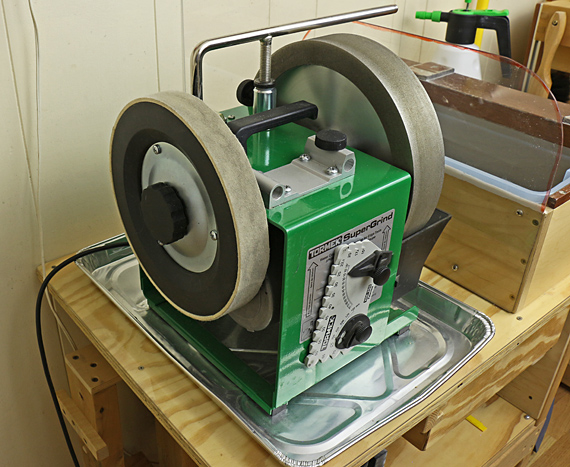

1. The blade may not be sharp enough, causing it to skid on the wood rather than cut it. The whole system (workpiece, plane travel, blade edge) may be deflecting, preventing the blade edge from engaging the wood.

Of course, end grain is harder to cut than long grain. Paring end grain is how many woodworkers test an edge. However, there is another reason why sharpness is so critical that is peculiar to shooting.

Planing in the usual manner with a bench plane, we intuitively sense that we can extend the working life of a gradually dulling edge by pressing down harder with the plane. Related to this, we find that it is necessary to advance the blade further (depth of cut adjustment) to get it to take the same shavings as when it was sharper, though with more effort. Eventually, we head back to the sharpening bench.

Brent Beach offers a technical discussion relevant to this. The basic idea is that the extremely narrow lower wear bevel in a sharp blade has less area against the wood, and so is able to generate more pressure (force per unit area) on the wood than does a dull blade with a wider lower wear bevel. The sharp blade compresses the wood and bites into it.

In shooting, the plane does not ride on the wood, it rides on the edge of the track, and so you cannot regulate the edge pressure against the wood as you can with ordinary planing. The blade has to be sharp enough to cut without your “help,” so to speak. Actually, I have found myself intuitively trying to shove the workpiece toward the plane as the blade dulls, but that is awkward at best, and tends to produce inaccuracies.

Furthermore, end grain is less compressible than side grain.

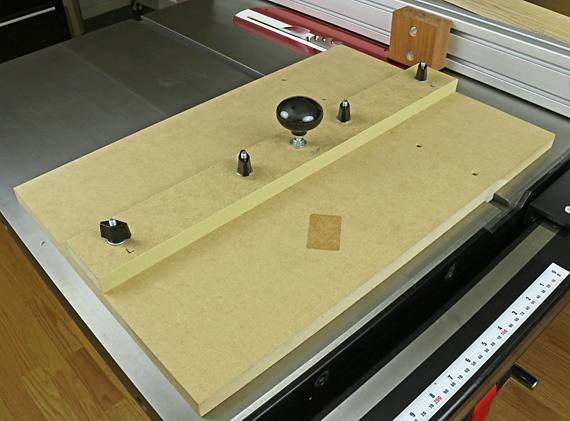

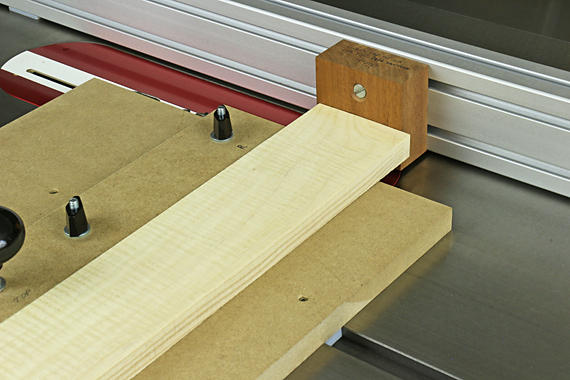

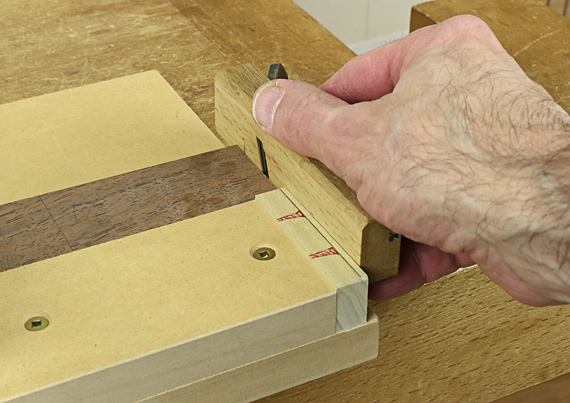

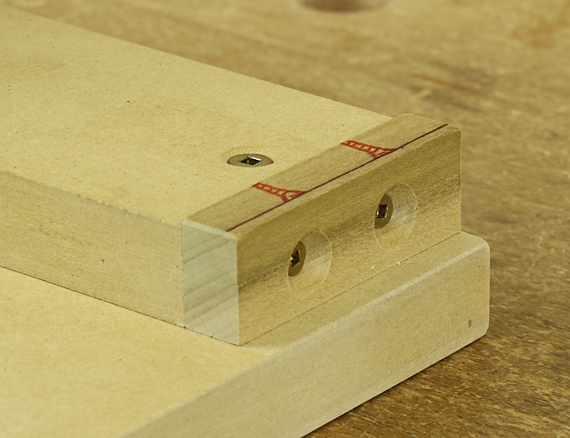

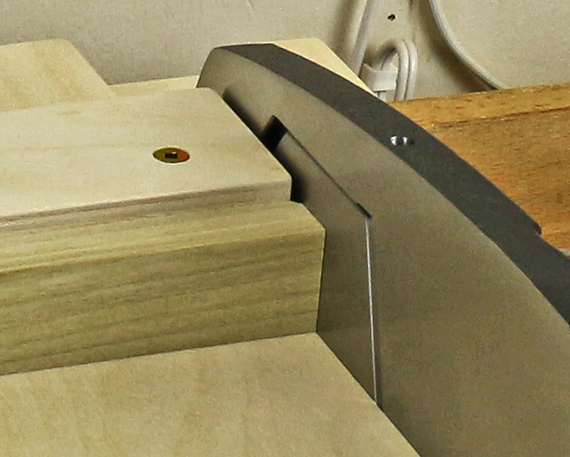

2. Another possibility is that the fence is set slightly greater than 90°. This will cause the workpiece to register against the sole of the plane near the fence but not reach the sole where the cut begins. It only takes, say, a couple thou of error for this to happen. Furthermore, as an insufficiently sharp blade moves along to eventually meet the workpiece, it might push it away rather than cutting into it. (This is another example of the general principle that a tool, hand or power, given the opportunity, will move the workpiece instead of cutting it, and/or move the tool itself.)

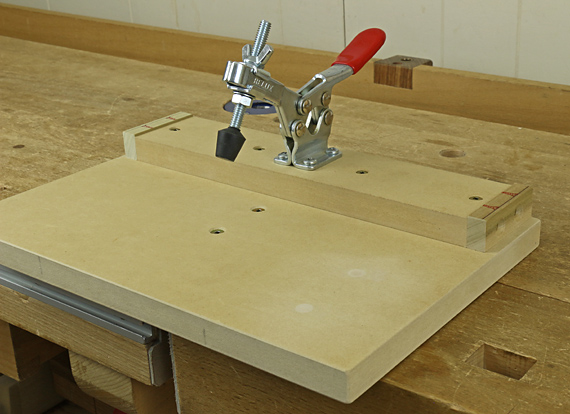

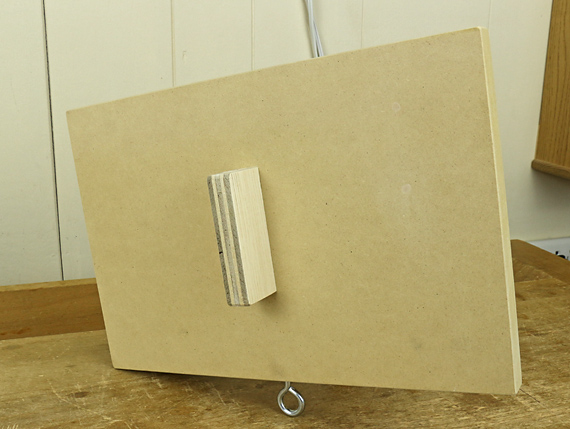

The shooting board fence may start out dead-on at 90°, but if it is not very firmly set, it is easy for it to eventually get pushed to greater than 90° because that is the direction of your force on it in use.

In summary:

1. Sharp – wicked sharp – is a must for shooting!

2. The shooting setup has to be not only statically accurate, but also dynamically stable in use.