Drawers must work throughout the year. There is no virtue in constructing an ego-feeding science project with a “piston-fit” in February only to find that you, or worse, a client, are unable to open the drawer in August. Let’s take a closer look.

In the “High-End Drawers” ten-part series on this blog that ran intermittently from July to November 2009, and in the article “4 Steps to a Sweet-Fitting Drawer” in Fine Woodworking magazine #224 (January/February 2012), I describe a reliable process for producing a good drawer fit. But just as with a good suit, a good drawer fit means not too tight and not too loose. With wood, however, we have the added complication of the inevitable changes in moisture content that occur with seasonal humidity changes. A zero-tolerance “piston fit” in February will be all wrong in August.

Let’s think it through.

Consider the width of the drawer in its case. In both solid-board and frame-and-panel constructions, the width of the case remains essentially stable throughout seasonal humidity changes, since it is defined and limited by long-grain pieces. Even the expansion of the side walls of a solid-board drawer pocket will occur on the outsides, not within the pocket.

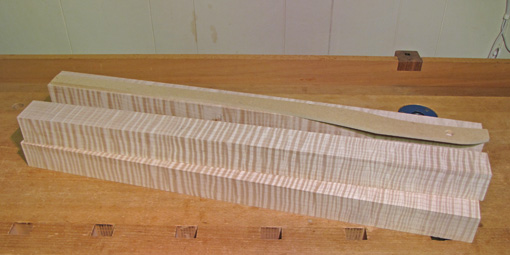

The drawer sides are oriented to expand laterally. (Their expansion in height will be discussed later.) As an example, hard maple, typically quartersawn for drawer sides, 3/8″ thick, will expand .012″ (12 thou) over a humidity increase from 35% to 80%. Drawer sides normally receive little or no finish, so these changes can, at least theoretically, occur rapidly. There are some mitigating factors though, including that the drawer spends most of its time secluded in the case, and the sides are somewhat bound by the joinery, usually dovetails. However, PVA glues retain some elasticity, as evidenced by the tiny elevation of tails above the endgrain of pins in very humid conditions. It should be noted, however, that this theoretical amount of expansion does not seem empirically to fully manifest.

Does this matter? Yes, it does. With the incremental construction method wherein the final step of fitting the drawer to its pocket is to plane the sides down to the level of the endgrain of the pins of the front and back, the drawer width can easily be fit to tolerances of a few thousandths of an inch.

So, if during the dry months, the drawer width is fit like a piston with a clearance of say a couple thou between the sides and the case, it is sure to be too tight in the humid months.

Is this all just theoretical? Not at all. I can tell you from experience that it matters. Years ago, during a low-humidity season, I made some nice drawers with a piston fit. I felt proud and thought that since they were small drawers, all would be fine during the coming summer, and I could get away with this exercise in ego-stroking perfectionism. Not so. The following August, neither drawer could be opened.

That is not practical woodworking. The perfect defeated the good. That Fall, I made things right.

Right now, in an August steam bath here in the Northeast US, drawers in pieces that I made several years ago operate well but with almost no remaining clearance. That’s fine. In the dry winter, the fit of these drawers do indeed have more play in width, but are by no means sloppy.

In summary, if you are building a drawer during very humid weather, fit the width to be very snug. If you are building a drawer in the dryness of February, you must leave some allowance.

Ah, but how much allowance should you make when building in dry conditions? It depends on the thickness of the drawer sides (less for thin sides), the species of wood, and the conditions where the piece will be housed. More play is appropriate in large, practical drawers than in small, delicate drawers. It helps to keep your shop from getting too dry in the winter. This will reduce the range of estimating that you have to do.

To avoid a stuck drawer, stay on the safe side but don’t go so far as to make a clearance that feels at all sloppy in dry conditions. For a small drawer, building in dry conditions, I like to at least get a sheet of paper, maybe two, in there on each side. Experience helps a lot; I go by how it feels. The theoretical expansion amount calculated above will be too much allowance.

Of course, haha, if your piece will be placed in a climate-controlled museum, don’t worry about any of this!

Next, we’ll look at the height of the drawer and appropriate clearances. That’s important too, but less finicky.