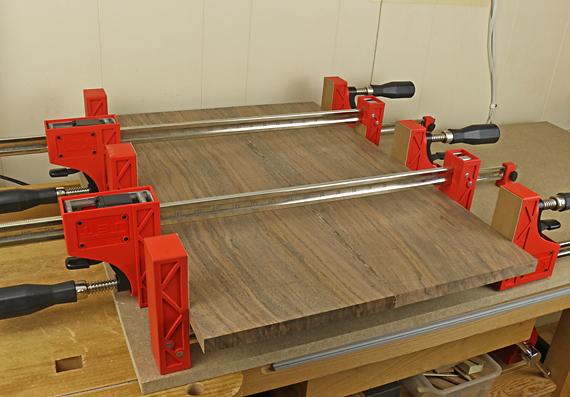

When gluing up edge joints, you want to maintain proper alignment of the boards to produce a flat panel. Especially for small shop woodworkers, it takes a lot of work to flatten glued up panels, which accounts for the proliferation of specialized clamps and devices designed to keep the boards aligned during glue up.

Maintaining alignment

The simplest reliably effective answer is a tool you probably already own: the biscuit joiner. Start with flat boards and good edge joints. Place #20, #10, or #0 biscuits typically 8-12″ apart and just a couple of inches or so from the ends. Remember to account for the trim allowance so you do not leave an exposed biscuit in a tabletop.

The most consistent results come by pressing the joiner’s fence against the reference face of the board, which is secured slightly overhanging the edge of the workbench. Even for “standard” 3/4″ stock, this is easier and more reliable than trying to register the board itself against the bench and using the sole of the joiner as a reference.

Make sure the fence is flat and exactly square to the joiner’s face. Test to make sure the fence is also parallel to the blade/slot and if necessary, shim the fence with tape to achieve this. You can even use a 5/32″ slotting bit in a router to make the slots if you don’t have a dedicated joiner.

The biscuits are not necessary for strength. A well-made edge joint is strong enough without them, though they can’t hurt and offer some insurance against imperfections especially near the ends of the joint. The goal is minimize the work of flattening the glued up panel.

Some authors recommend hammering the boards into alignment during glue up. With the partial exception noted below I do not like that method. Time is very limited once the edges are brought together. Using a hit or miss process while playing with clamp pressure, rushing, and hoping are not my style of woodworking, particularly when a very fast and reliable alternative is available.

At glue up, squeeze glue in the slots before spreading it on the joint edges. If you reverse the order, the coat of glue on the edge has time to start skinning over while you are fiddling with the slots. Another option is to forgo gluing the slots, but why?

Later, when you are ready to plane or sand the panel, remember to avoid sunken areas above the biscuits by giving the extra moisture and consequent wood swelling time to dissipate. Use a pinless moisture meter or just check for remaining swelling with a small rule. Anyway, before working the surface of the panel, you have to wait for the immediate area of the glue line itself to loose its swelling but this small added delay for the biscuit areas is about the only real disadvantage of using biscuits.

I do not use any of the following: special over-under clamps, cauls, pinch dogs, dowels, Dominos, splines, or incorrigibly distorted wood that does not belong in a panel.

Thin panels

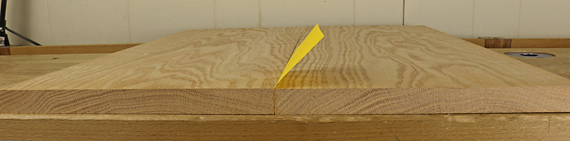

What about thin panels such as drawer bottoms that will not accommodate a biscuit? Here is a straightforward method using simple shop-made blocks to control the boards near their ends that will cover most of those situations. Depending on the length of the panel, a bit of tapping in the interior of the joint is usually necessary to align the boards but this is usually easy because it is a small panel with relatively light clamp pressure.

For shops that need to make lots of panels efficiently, such as dining tables and large frame and panel doors, the Plano Glue Press is one specialized tool that looks worthwhile.

The other major aspect of reliable alignment is clamp set up, which we’ll look at next.