In managing the fit of the height of a drawer in its housing, the seasonal changes are larger, and thus not a matter of such fine tolerances as with the width which was discussed in the previous post. Let’s take a closer look.

A four-inch high drawer front in flatsawn solid maple will expand about 1/8 inch when the ambient air goes from 35% to 80% relative humidity. For flatsawn cherry or walnut, the change will be about 3/32 inch. For quartersawn wood, the values will be about half to two-thirds of those. Wood finishes will slow but not eliminate these changes, as shown by the work of the US Forest Products Laboratory.

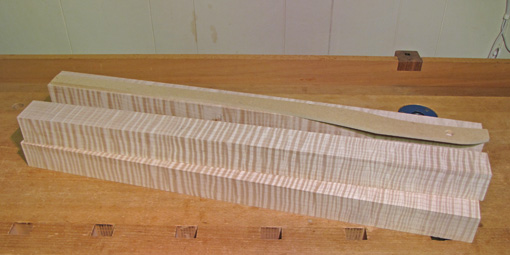

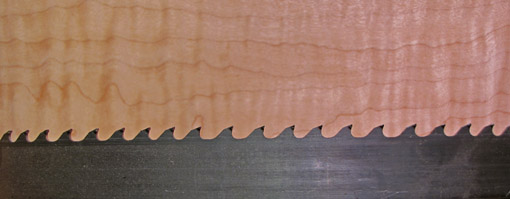

If you are building inset drawers and the humidity in your shop is at the low end of that range, allow those amounts of clearance from the top edge of the drawer front to the divider or case member above it. If the drawer is eight inches high, double those clearance amounts; for a two-inch drawer, halve them. (The drawer in the photo is just over two inches high.) The tops of the drawer sides are made flush with the front, while the top edge of the drawer back is made a bit lower than the sides.

This means that during the dry season, the clearance space above each drawer front in a group will be proportionate to the height of the drawer. This will look odd only to those who do not understand wood. For overlay or lipped drawers, appropriate clearance must still be made but it is, of course, hidden by the front.

Remember too, the depth of a solid-wood case with the grain running vertically will similarly change with the seasons, and thus the length of the drawer must be calculated for the time when the case has the shortest depth, plus a margin of safety.

Woodworking lore and some authors extol “piston-fit” drawers whereby pushing in one drawer in a set will cause others to be forced outward from the resulting air pressure within the case. Well, this can be done and is not very difficult to accomplish. For fun, you might try it on the way to building useful work. To me, “piston-fit” implies virtually zero clearances – which may work for small drawers at one particular time of the year, but not for practical woodworking. Proper clearances for the sides, front, and back that render a drawer functional year-round preclude a true piston-fit. It should not be considered a hallmark of top-quality drawers.

Really, you’ll feel much more comfortable when your drawers have a practical fit.