Will the PM-V11 blades made for Veritas standard bevel-down bench planes work in a Lie-Nielsen plane? These are nominal 1/8″ thick blades, the same thickness as the L-N blades. I am not referring to Veritas PM-V11 blades made for “Stanley/Record planes,” which are .100″ thick (a little more than 3/32″).

Manufactured by Lee Valley/Veritas, PM-V11 is a wonderful steel that I’m glad to have in my Veritas bevel-up planes. Veritas offers lots of information about it, including their extensive testing, in a dedicated website.

First, here are my impressions from using PM-V11 blades in my LV BU planes. Though obviously not scientific, they differ somewhat from Veritas’ testing.

For ease of sharpening, Veritas found PM-V11 about the same as A-2 but, as we would expect, not nearly as easy as O-1. My sense is that PM-V11 is actually noticeably easier to sharpen than A-2. I don’t think it actually wears faster on my CBN grinder, diamond bench stones, and 0.5 micron ceramic finishing stone, but somehow I feel more confident in creating a reliable final sharp edge. This is completely subjective and perhaps is just a matter of how the steel feels on the stones.

As to the sharpness of a new edge, it’s hard to beat O-1 but I think A-2 can get pretty close. PM-V11 seems to me to be even closer to O-1, and probably equal. Again, this is subjective and perhaps is more of a matter of ease and reliability in getting to a pristine final edge.

Regarding edge retention, it seems odd that the Veritas testing found that A-2 barely beat O-1. With the caveat that A-2 blades vary considerably, I think most woodworkers find as I do that A-2 holds its edge significantly longer than O-1. My unscientific sense is in general agreement with the extensive Veritas testing that the edge in a PM-V11 blade indeed outlasts most A-2, though not by as wide a margin as Veritas found. I think the Hock A-2 blade that I have in my jack plane would give PM-V11 a run for its money. Still, you’ve got to respect the extensive testing that Veritas has done.

In short, there is good reason I’d like to use PM-V11 in my bevel-down Lie-Nielsen planes, which are, of course, absolutely fantastic planes.

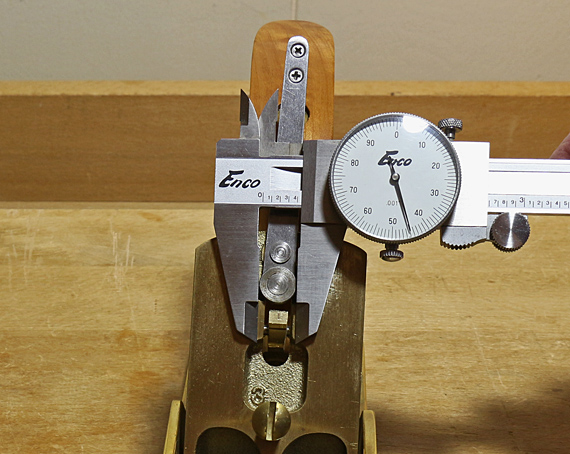

In my L-N #4, the lateral adjustment button measures .445″ across. The slot in the L-N O-1 blade that I own is .455″ wide, and .452″ in my L-N A-2 blade. The slot in the Vertias PM-V11 was .441″ when I received it.

I simply widened the Veritas blade slot to .446″ using a 2″ x 6″ DMT extra-coarse diamond stone and cleaned up the resulting harsh edges with the other (coarse) side of the stone. Though this results in just minimal clearance of the slot around the adjustment button, the blade beds just fine. In fact, the reduced play in the lateral adjustment mechanism makes it a bit more responsive.

The Veritas PM-V11 and Lie-Nielsen blades are virtually identical in thickness (within one thou) at about 1/8″. There is no need to compromise by using a thinner blade. There is also no problem connecting the chip breaker, nor with the fit and function of the blade advancement pawl. The slot in the Veritas blade is longer than in the L-N blade but that does not matter as far as I can tell.

I think now I’ve got the best of both of these great companies in my good old #4.