This installment of the Q&A features questions from readers about shop electrical supply, convex-sole planes, gel varnishes, ripping, and Claro walnut.

A woodworker who is planning a new small shop is considering how much and what type of juice to have the electrician wire into it. Here’s what I use in my little playpen and why.

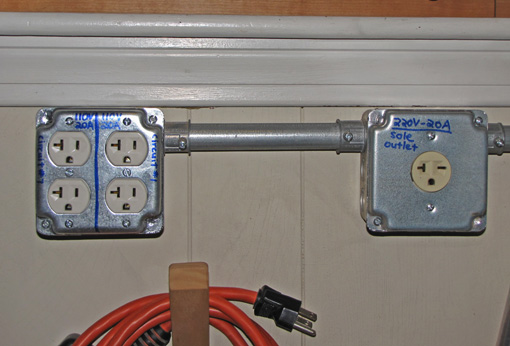

The pre-existing wimpy household 110V-15A wiring takes care of shop lighting and a few other small items such as a battery charger. Then there is a 220V-20A line with a single receptacle. This runs the bandsaw, table saw, and jointer-planer; one machine at a time, of course, because there’s only one guy in the shop. A 220V-15A line would not reliably handle a surge from the jointer-planer rated at 14A or the cabinet saw at 13A. There are also two 110V-20A lines, each with a pair of receptacles. Two lines are necessary to run the DW735 at 15A along with the dust collector at 16A. This also accommodates any portable power tool that I own along with the Fein shop vac.

It pays to plan carefully for the shop you have now and for the shop you aspire to. I think I’ll never need more juice than this in my one-man small shop.

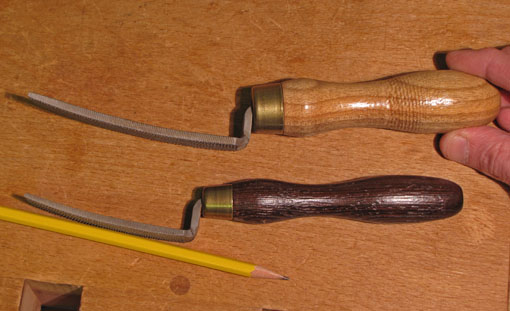

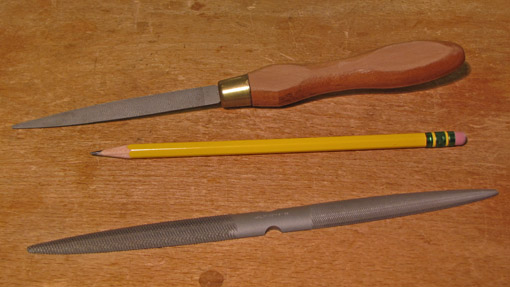

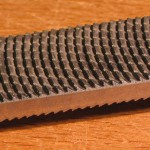

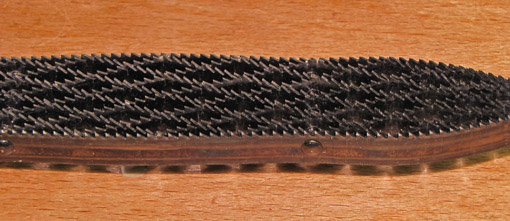

A woodworker planning to make a coopered door inquires about options in planes with the sole and blade convex across their widths. The radius of the blade needs to be just a bit smaller than the curve it planes. Calculating an example, a 14″ wide door with a curve depth of 2″ has a radius of 13.25″. A 1-1/2″ wide plane blade of this radius will have a curve depth of 0.02″. Taking into account the effect of the blade bedded at 45 degrees (formula here), the blade must be cambered .03″, or about 1/32″. A tiny bit more depth than that will keep the outer corners of the blade clear of the wood and enhance control.

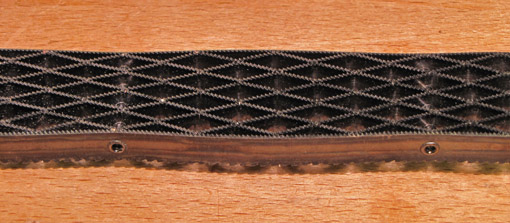

For this, my solution is to take any small wooden plane and camber the blade, and shape the sole to match it. Test and adjust. One nice option might be to get a Krenov style plane kit from Ron Hock and alter it accordingly. A Japanese convex sole plane is a more expensive option that is not tailored to the specific task, and is likely to be too curved for it.

I was a fan of Bartley’s gel varnish, which is no longer available as far as I know. A few questions came in regarding alternatives. Here are three:

A reader asked about my preferences in handsaws for long rips. My preference is the bandsaw, the “hand tool with a motor.” In most cases, I see no particular virtue in sweating out a long rip by hand, but the Disston D-7 is my weapon of choice if I really want to commune with the wood.

Speaking of communing with wood, I’ll hang out with Claro walnut any day. A reader wonders what woods might make a good combination with Claro. Of course, this is personal preference, but consider pear. The pink blush of pear seems to bring out the red hues in Claro, and its fine, delicate texture contrasts with the moderately open-grain nature of Claro. Unity and variety, right Mr Heath?

One combination that might seem promising but falls flat to my eye, is walnut and cherry. Maple and walnut usually don’t seem to work together. Claro and zebrawood look cool together, and ash also has potential with Claro. Just opinions.

Email questions (see the About page) and I’ll try to answer as time permits. Thanks, and happy woodworking.