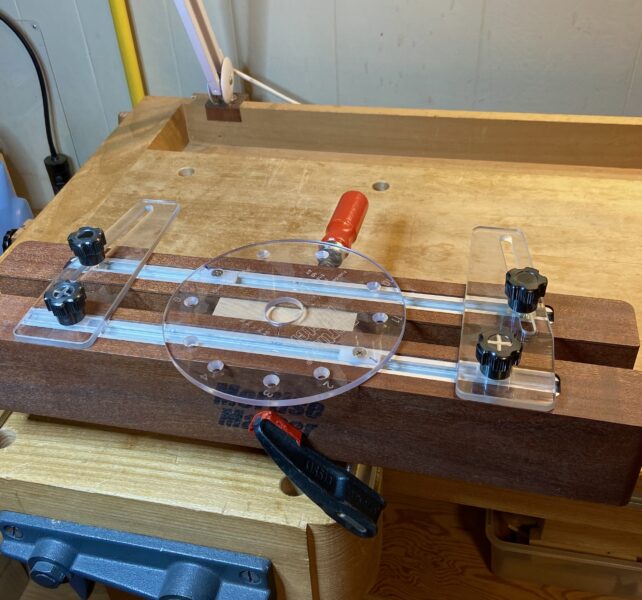

Consider the strength of the end to side-edge joinery which we have put into three categories: mortise pair and free tenon, Domino, and dowel.

When did you see a properly made joint fall? I never have in my work. The dowel joint gets the most criticism regarding strength. Let’s discuss that.

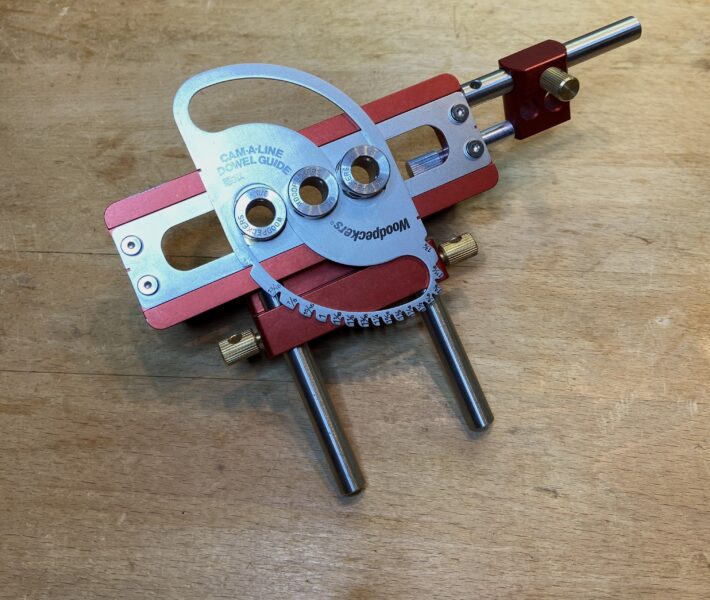

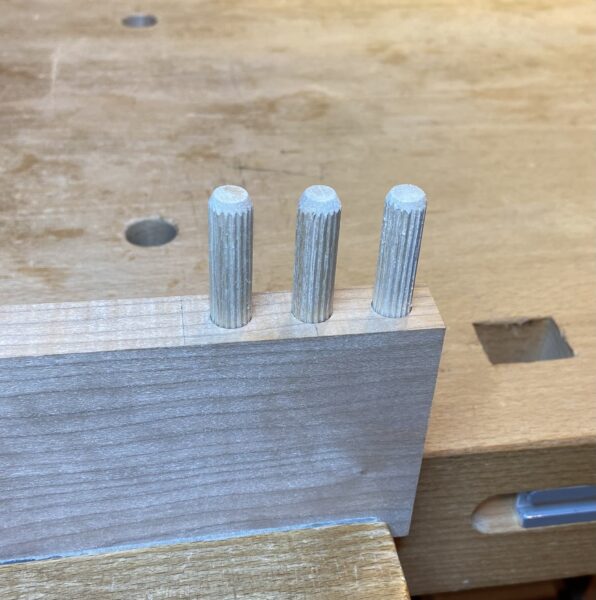

As an example, consider a 2 3/8” dowel joint with three 3/8” dowels that are set 3/8” apart and 1/4” from the edges. (As above photo.) We only need to examine the cross grain part of the joint. The other half – dowel grain entirely inline with the wood grain – will really not break for practical reason.

Based on the number of dowels and their diameters, the total glue width is 3.5”. As a mortise joint, we are gluing 3.9” width. This assumes not applying glue to flat or curved outer tenon edges to allow space for a bit of seasonal movement. Nor would the bond grip well there. We also assume the depth of the joint is the same for dowel and mortise.

Also, note that some of the dowel side area, though entirely glued, does not grip as well since it is attached to opposite grain direction. It is hard to say at what stage of the circle this changes for better.

So, the dowels use a little less glue joint area than mortise joints, but not much. Working out a similar example using 1/2” dowels in a 2 1/2” wide joint, gives 4.7” of glue width. The mortise joint has less at 4” of width.

By the way, wedged tenons – either at the central end or on the sawn and angled wide sides – have a distinct strength advantage. For that we have to award the strength contest to mortise and tenon.

Basically, to compare mortise and tenon joints with properly made dowel joints is a close call for strength in my opinion.

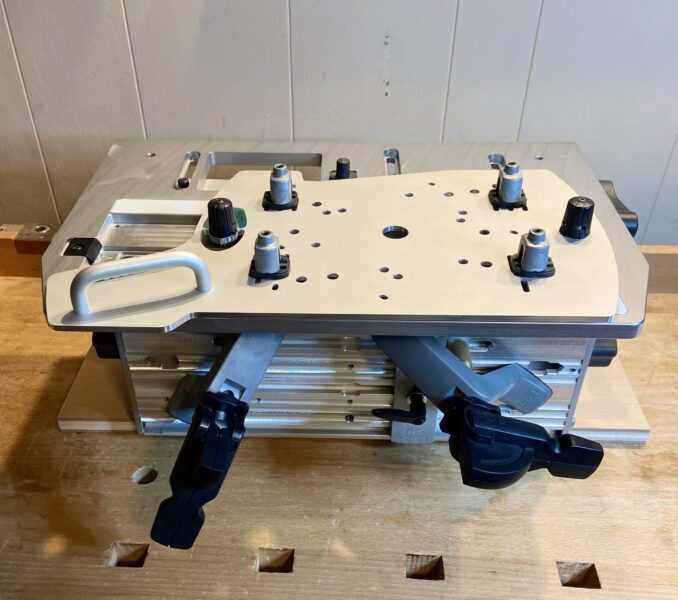

The best joint strength contests that I have seen online are done by the DowelMax. They look careful and legitimate. Dowel joints win. Dominos come in third place.

All of this is not a science project. I simply am saying that joint strength is not a good reason to oppose dowel joinery. Again, it must be properly done, like all joinery.

Let’s give the appropriate, but commonly opposed credit to dowel joinery: strength. It also is convenient, fast, and cost efficient for good tools. Pieces that I have made months ago as well as decades ago with plenty of dowel joinery have never failed!

Once again, I list the three main joints I use and recommend for woodworking: Pair of mortises with free tenon, Domino, Dowels.

But which of the three have I now come to choose most of the time? The answer is coming but anyway, my choice may not be your best choice.

Having a realistic practical choice is what matters for each woodworker. Hopefully this series helps you choose.

More to come.