Now things get more tricky. If you have been avoiding angled joints, or maybe you tried and messed up a few (hey, I think that is everyone who has tried them) I want to put them in general categories with different levels of potential difficulty.

This is not to show detailed, step-by-step processes. Rather, I just want state the general ideas from which you can develop your specific methods.

So let’s start with the easy group. This is where the joint angle goes across the width of one or both pieces. The length of the piece is simply cut at an angle, ideally on an accurate table saw crosscut jig.

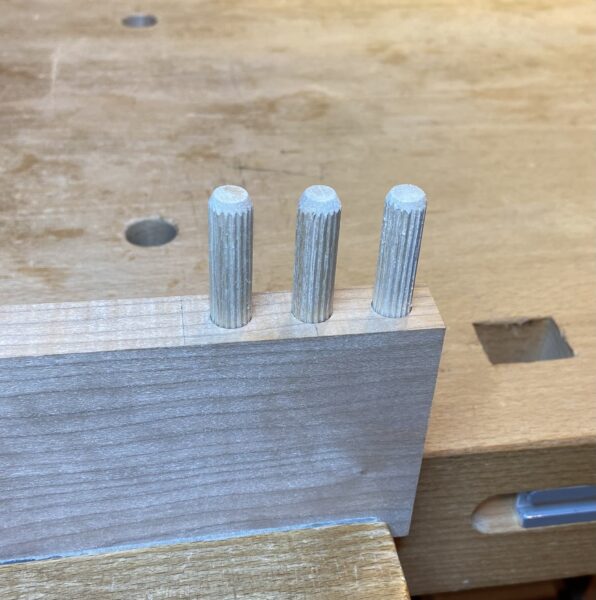

The photos below show two examples. One is a piece with a 90° edge matched with a piece with an angled edge. The other is a pair of pieces that each have an angled edge.

No problem. These can go directly to your dowel jig, Domino, or mortising jig. Plan the position and length of the holes or mortises. They are cut at 90° to the angled edge of each piece.

Now it gets harder. The angle is at the edge of the thickness of one or both pieces, placed at the end of the length of the piece(s).

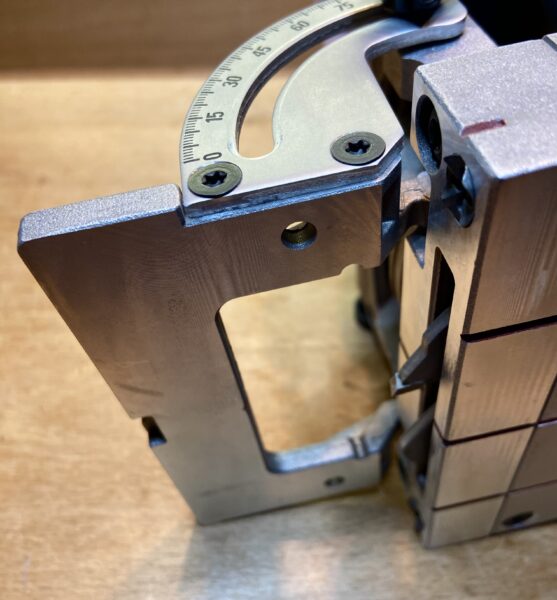

The photo at the top of this post shows the angled edge of each of two pieces. The angled piece can be joined to another angled edge or simply to a flat edge.

The first photo below shows a pair of angled end-grain edges across the flat width of each piece.

The next photo below is to imitate a chair joint. (To make the photo of the unassembled pieces easier, I placed the “chair” upside down.) The angled-end piece, at 2°, meets the long grain of the “chair leg”.

These are examples of where things get trickier to make. Why? Because we have to join the angled edge to a flat surface. The flat surface can simply be square to the board as in the two photos below, or can be an angled flat surface of the other piece. The joint cutter must be at the angle of the angled piece(s).

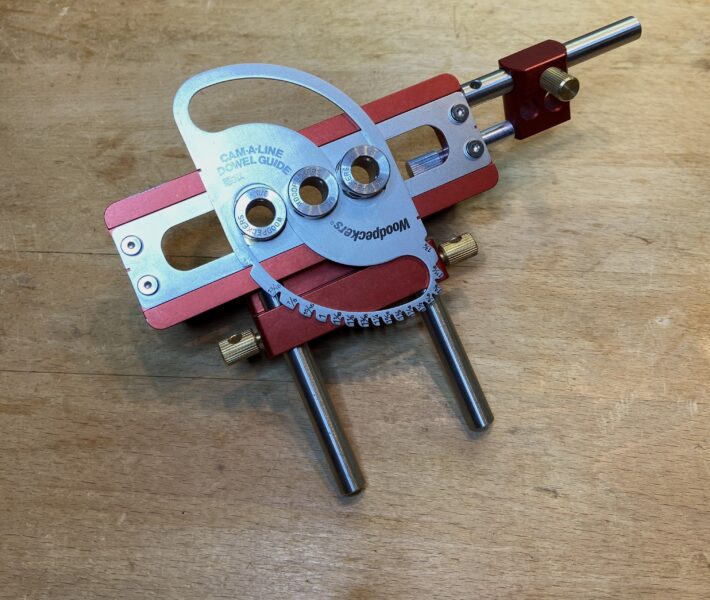

For this job, there are many options. Domino can work well, though there must be good placement and grip of the machine. Any angle can be set. DowelMax makes a doweling jig, though it works at only 45°, which will build a box or similar items. The Leigh FMT and Woodpecker MultiRouter (both are expensive, as are Dominos) can do a really nice job. I suggest making a pair of mortises and a free tenon for an easier job. The Leigh FMT works well for me for this task. It is precise and reliable. The PantoRouter looks like it also could certainly do the job.

JessEm has a Doweling Jig Workstation. I have not used it but I was not impressed by what I saw online, along with the related (?) Pocket Mill Pro. There is also many other machines that can do this task, many high priced, which I am not familiar with.

What about angling a conventional drill press? Yea, maybe, but getting perfect, steady angles that give good joint matchup is difficult. Not my choice. I also suppose something could be worked out with a benchtop mortiser, but I have never been a fan or owned one of those.

With all of this, remember that you are cutting square to the joint surface of the angled piece(s) and the square-edge of the other part of the joint if that is how it is set up.

With good equipment and planing, we can reliably make these joints!

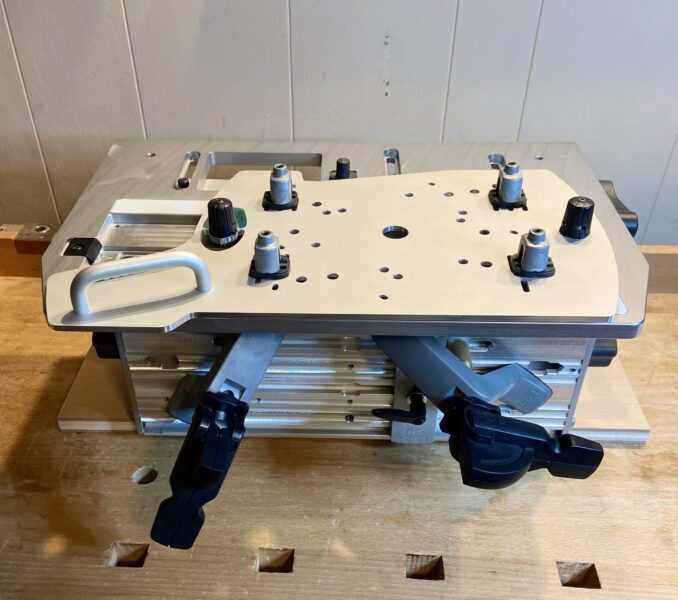

Now, there is one more problem. Though I have done it in building, I have to say it is difficult. This is when a part of the joint is curved AND has an angled edge. With a tenon, or a mortise and a loose tenon, it meets a flat surface. The photo below shows an example.

Sometimes, this can be done when the wood has not yet been curved on its main surface, but not always. Sometimes handwork is the best and fastest way. It does take careful work!

Well, we’ve done it! We have covered a full range of joinery that I have labelled as “end to side-edge joinery.” Again, the idea of all of this is to organize the workable, practical systems and tools that allow you to choose how you can comfortably and effectively guide your woodwork. I think that the age of the traditional mortise and tenon is largely over for most woodworkers.

I hope it helps!