Yes, humble poplar. OK, this is not a species that is likely to evoke lust, but it is a good wood to love. It should not be overlooked for a supporting or occasionally major role in high-end work, as well as duty in utilitarian work.

To be clear, the species under discussion is Liriodendron tulipifera,whose common names include yellow poplar, and, with a bit more cachet, tulipwood and tulip poplar. This is distinct from similar woods: aspen and cottonwood (Populus spp.), willow (Salix spp.), and basswood/lime (Tilia spp.).

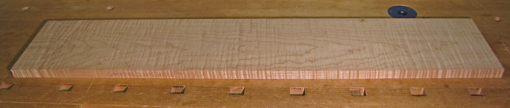

Friendly, inexpensive poplar is readily available. My local orange-themed home center carries plenty of dry, dressed 3/4″ thick boards, as wide as the 1 x 12’s pictured below, and sometimes thicker stock. At my local hardwood dealer, sound stock up to 16/4 is available because poplar dries easily and with minimal degradation.

Poplar heartwood is usually pale yellowish green after milling but eventually changes to light brown after exposure. Some boards have deep purplish, green, or other color mineral stain streaks in the heartwood. The sapwood is creamy whitish which tends to develop a tinge of tan. I’ve never seen figured poplar but maybe it’s out there somewhere. It is a modest wood that, in my opinion, is best appreciated for what it is. Attempts to stain it to imitate another wood, such as cherry, end up looking lame to my eye. An exception may be when it is dyed black (ebonized) for use as an accent wood.

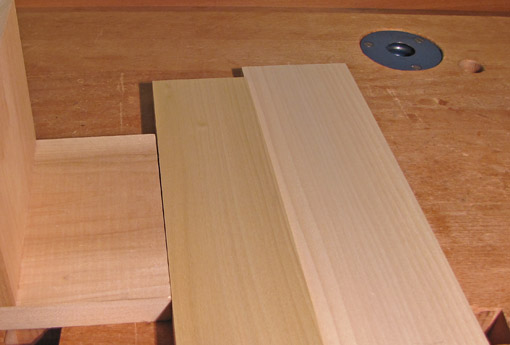

Below, left to right: aged poplar, fresher heartwood and sapwood.

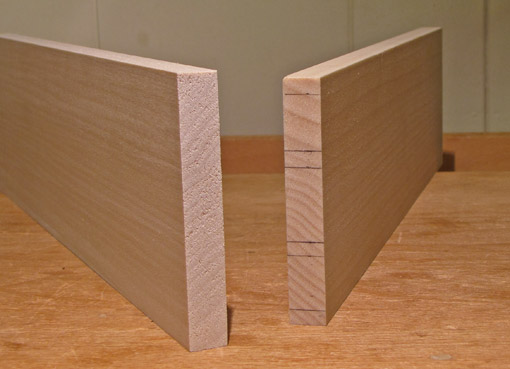

Poplar, oh, yea, I mean tulipwood, makes a great secondary wood in fine work. It is hard to find quartersawn, but rift grain for drawer parts and panels can be salvaged from wide flatsawn boards, as seen in the photos below. For novice woodworkers – and we’re all beginners to the extent that we explore and learn new skills – poplar is an easygoing wood that can still yield very nice results. It saws, planes, and glues easily. Its fine texture takes paint well.

For utility work, such as storage units, and for many shop fixtures and jigs, poplar is usually my first choice. I also use it very often for mock-ups.

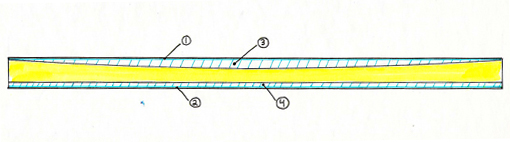

Poplar is a fairly stable wood with tangential and radial shrinkage values of 8.2% and 4.6%, respectively, T/R is 1.8, and volumetric shrinkage is 12.7%, making it certainly more stable than sugar maple and the oaks. It is a light wood, having an average density of 0.42, and surface hardness less than walnut and cherry but greater than white pine. It would suffer as a heavy-use table top.

Surprisingly, though, its stiffness (modulus of elasticity) exceeds that of cherry and big-leaf maple, though it is no match for sugar maple or the oaks. In this respect, it is a better choice for bookshelves than pine, which is considerably less stiff. For its density, poplar has good strength in tension perpendicular to the grain, which produces resistance to splitting, about the same as cherry and big-leaf maple, and much better than pine.

For lots of woodworking jobs, poplar deserves consideration. And some love.