Next up is khaya. The wood available to us may be any of four species in the Khaya genus: K. ivorensis, K. grandifoliola, K. anthotheca, and, less so, K. senegalensis. Ask the guy at your lumber yard what species he’s selling and he’ll probably look at you the same way we look at an 88° try square, even if the importer had kept the species distinct. In fact, you’ll probably create confusion by asking for the “khaya” bin because it is more commonly referred to as African mahogany.

And so, this is the only wood comparable to genuine/true mahogany (Swietenia) that generally bears the “mahogany” name. Botanically, it is in the same family (the next major grouping above genus), Meliaceæ, as Swietenia. It comes to us from West African countries.

Just like true mahogany, when African mahogany/khaya is good, it is indeed a very good wood. The problem is that I have had just as much frustration with inconsistency in density and color in khaya as with true mahogany. There is variation among species, but also with the geographic source of the tree, and the local conditions in which it grew. Therefore, as a practical matter, I suggest that you not be too concerned with the provenance of the wood, but evaluate each board on its own merits. Khaya is about half the cost of true mahogany, and there is some great stuff available.

Some khaya is less dense, and quite light in color – an uninspiring pale pink hue. The flatsawn wood looks particularly anemic. When quartersawn, these boards often have a hairy surface that can be difficult to finish. They come off the planer with hairy rows that are hard to tame with planing, scraping, or even sanding.

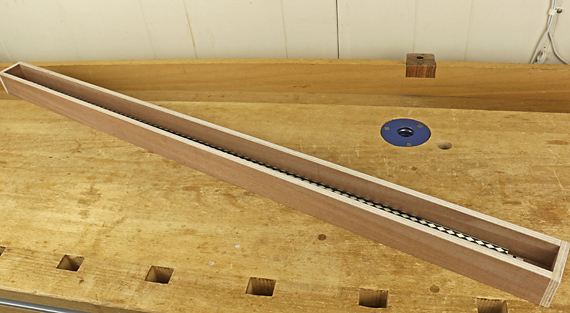

I try to avoid these boards and instead look for darker, denser boards. Many quartersawn khaya boards exhibit a fairly coarse, beautiful ribbon stripe. The boards in the photo at top are a good example of dark khaya with great ribbon stripe. Look how nice it finishes:

More quartered African mahogany:

The color below is a bit more red but also very nice:

Good flatsawn khaya is also very worthwhile. In some case, it is difficult to distinguish from high quality true mahogany. In general though, I’ve found that true mahogany’s legendary chatoyance is harder to find in khaya.

Unfortunately, khaya seems to be quite susceptible to the dreaded compression failures that I discussed in reference to mahogany in the previous post. With the possibility of these defects, as well as the great variation in the other properties of khaya, I suggest buying your boards S2S planed or hit-or-miss planed, if possible. Look them over carefully.

Coming up: sapele and others.