Sharpening is so much at the core of hand tool woodworking, and so here are a few thoughts that build on the previous post on sharpening tests.

1. Can we close the loop and say that the proxy tests are actually validated by the tool’s performance? Based on experience, yes, regarding sharpness, edges perform as the tests predict. The tests are worthwhile.

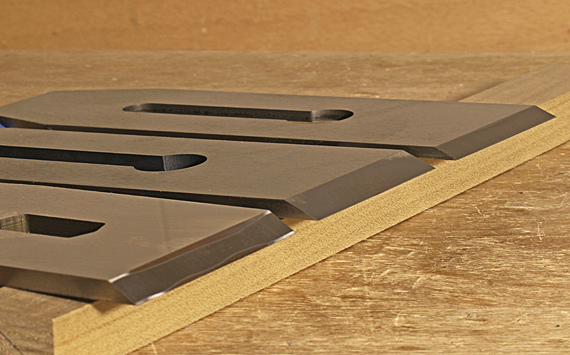

2. Edge endurance, however, is another matter. There you are relying on the “design” of the edge and the reliability of your sharpening process. The only “test” is over time – seeing how long the edge lasts. For good results, you must match the edge geometry to the steel and the task.

For example, A-2 is a good choice of steel for a jack plane blade but if the bevel angle is too narrow, such as would be good for O-1 steel, the edge will be prone to premature chip-out.

As another example, a plane blade with a wide bevel angle (e.g. 43°), though correctly employed in a bevel-up plane to create a high attack angle to reduce tearout, will necessarily have a shorter useful working life than narrower edges.

3. Squareness or, as appropriate, the correct skew angle, is, of course, easy to test. By the way, I find that a chisel edge that is just a bit out of square is not a big deal, as is sometimes supposed. There’s also a bit of squareness tolerance in most plane blades.

4. For many woodworkers, the most vexing matter of edge geometry is plane blade camber. For choosing, producing, and assessing camber, I invite readers to visit this series of five posts, which is about as in-depth a treatment of the subject as I think you will find anywhere.

Stay sharp, amigos.

I’m curious about your second edge-endurance example. I have never heard that a larger bevel angle would have a shorter working life than a narrower angle. Can you explain further?

Hi Carl,

Here’s my intuitive explanation. Imagine you are trying to dull an edge by abrading it with sandpaper to the point where you can’t cut your finger with it. Which edge would become wide enough to get to this point sooner: a 25 deg bevel or a 45 deg bevel? They may start out equally sharp, i.e. a very narrow “nothing” edge, but the 45 deg bevel would widen (dull) faster.

The most succinct description of wear bevel issues that I’ve ever read was very recently, an article by Terry Gordon in Furniture and Cabinetmaking magazine, issue#276 (November 2018), pp. 48-51. There are long articles on Steve Elliot’s and Brent Beach’s sites but the article I cited explains it elegantly.

In practice, there’s no question for me – when I use I big fat bevel angle (e.g. 45 deg) in a bevel-up smoothing plane to reduce tearout, it dulls fast. It works great when it’s fresh but not for long. By the way, there’s another issue, which is the loss of clearance angle in that situation. Terry explains that beautifully as well.

This is one of those things that’s true in theory and true in the shop.

Rob

By the way, the issues of wide bevel angles and low clearance angles creating a faster loss of functional sharpness are yet more reasons why it is, in my opinion, just plain wrong for bevel-up planes to be bedded at 12 degrees, as almost all of them are (the exceptions being among a few boutique makers). I would like write about this again soon. Who knows, maybe the Lees will eventually see it my way. Ha.

Rob

Rob,

You have a wonderful web site here with a wealth of information. I have been a woodworker for many years and I am just now finding your Blog. Thank you so much for making this available.

Eric

Eric,

I hope you find it useful and enjoyable. Your comments are welcome.

Rob