Almost all the woodwork I make contains several curves. In fact, a key curved component, such as the legs of a table, is often the initiating design idea.

My usual approach to making curved parts is much like an athlete competing in a sport – lots of organized preparation followed by trusting the instincts when the time comes. For a table leg, for example, the work progresses from sketches, to mockups, measured drawings, careful construction of a template, milling a squared blank, and marking out the blank. Then I carefully bandsaw the curves up to the layout lines, but never destroying the lines.

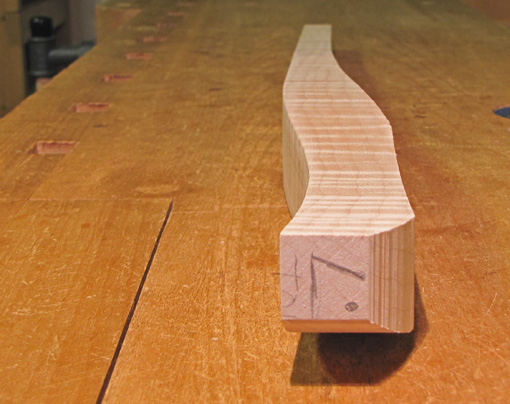

Next comes “fairing” the curve – eliminating lumps and valleys to produce a smooth, pleasing curve. At this stage, working to the layout lines may be helpful but is definitely not sufficient to get the desired smooth curve. This is game time – you must trust your senses.

Look and feel: use your eyes, hands, and tools.

I am going to describe these in reverse of the order that they are used in fairing the curve. In practice, there is a dance among these techniques. (The examples pictured in this post are in various stages of formation.)

Look

Position your eye near the work piece and sight along the curve, preferably against an uncluttered background. This vantage point makes aberrant bumps and troughs easy to see. Reach out and mark them because they will no longer be so obvious when you move away. You will know when the curve is right – it flows without doubts.

For my taste, the most interesting curves do not have a constant radius or are even portions of an ellipse, but are born of intuition with a rightness that is plainly and satisfyingly evident.

Feel

When the work piece is dogged in position for shaping on the bench, the working face is usually upward, making it awkward or impossible to do the look test. Repeatedly unclamping and lifting the work piece or bending yourself into awkward positions gets tedious. Therefore, use your fingers to test the curve quickly and frequently as the work progresses.

Here’s how to use this often-underestimated sense. The fingers may be tense and slightly desensitized after gripping a tool, so take a moment to reawaken the touch receptors by shaking or lightly fidgeting the fingers. Then “calibrate” your fingers by lightly swiping them on a clean area of the flat surface of your bench. Brush debris off the curved work surface. All this takes just a few seconds.

Now lightly “ride” the curve on the work piece with your fingers. The fingers should be mostly relaxed but with just the slightest tension to feel the changes in the ride caused by bumps and valleys. On concave curves, I find an uphill ride to be more sensitive than a downhill one.

I think you will find this to be remarkably sensitive. This is like tuning a musical instrument – don’t predict the next moment of sensory input, just let it in. Gradual deviations of less than 1/64-inch can be felt. You can check the look test to see how the two methods correlate.

However, along with these tests, it is necessary to feel what is happening under the tool as you are working, moment by moment, so you can efficiently remove wood with intent and direction. In the next post, I’ll discuss the tools that I find effective for fairing curves, and also why some common tools do not work so well.

Hi Rob-

First thanks for the blog.

I love that you posted this.

I’m a very novice woodworker, and make solidbody electric guitar bodies principally (or I would like to).

This is exactly how I smooth off the body – by feel. Your hands know!.

Thanks!

i agree wholeheartedly – sense of touch is critical here. i noticed that feel is how i judge the finish point for a lot of woodworking – joinery, flatness (where not mechanically critical), and finish, not to mention smoothness of curves. One of my first inclinations when i see a nice piece of woodworking is to want to touch it, and that touch has to feel right, otherwise the effect of the whole is diminished.

Speaking of which, that last pic of the carved mahogany almost makes me want to poke the screen. I bet it feels like butter :-)

Martin,

Thanks for reading. Good luck with the guitar making. Must be in your blood with the name Martin!

Aaron,

Yea, one of the wonderful things about woodwork is how it draws in the sense of touch. I think more than any other material – metal, glass, clay, painting, plastics, etc.

Rob